The emergence of organoids has allowed researchers to transcend the limitations of two-dimensional cultures, enabling them to explore the uncharted mechanisms and the intricacies of morphogenesis in organisms more comprehensively and from a higher level. However, current organoid culture technology still faces significant constraints, with the majority of organoids being monolayer organoids derived from epidermal stem cells, which greatly limits their ability to simulate the human body.

Recently, the team led by James M. Wells at Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center published an article titled "Functional human gastrointestinal organoids can be engineered from three primary germ layers derived separately from pluripotent stem cells" in the journal Cell Stem Cell in December 2021. In this article, they presented their newly developed three-germ-layer organoids and outlined their plans to further explore the roles of different tissue structures in the development of the stomach based on these organoids.

All organs of the gastrointestinal (GI) system are assembled from cells originating from the three germ layers during embryonic development. The normal development of the GI tract and the execution of its numerous complex functions rely on the interactions between the three germ layers and the organs they develop into. The gastric wall, from the inside out, consists of the mucosa, submucosa, muscularis, and serosa, encompassing epithelia and glands derived from the endoderm, smooth muscle derived from the mesoderm, and the intramural plexus of nerves derived from the ectoderm. Damage to any of these components can lead to various complex congenital or acquired diseases. However, currently, the construction of gastric organoids is limited to monolayer organoids containing epithelial tissue, resulting in poor simulation of the complex human structure, and there is an urgent need for the construction of multi-germ-layer organoids.

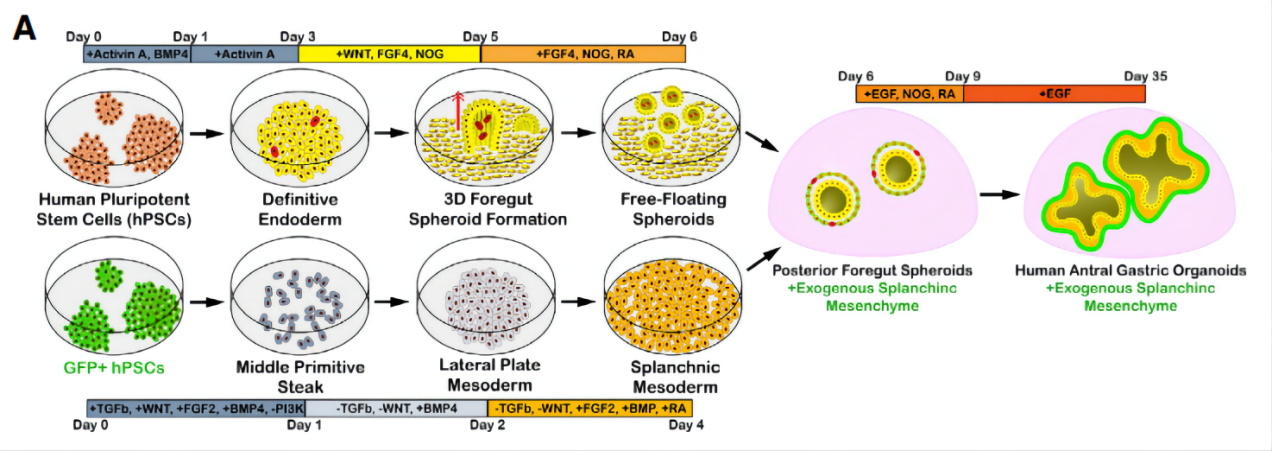

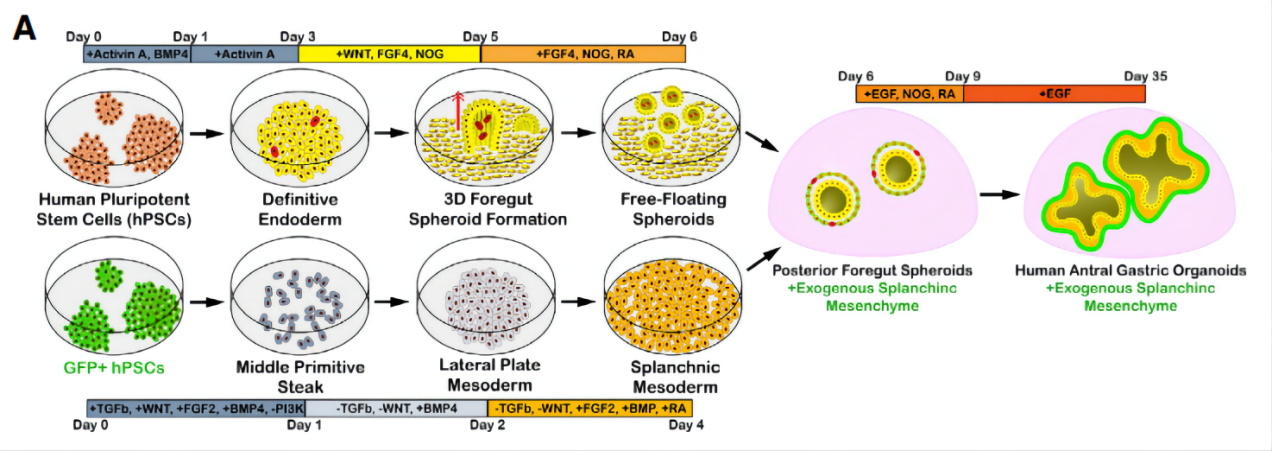

First, the authors combined mesenchymal cells derived from the mesoderm with epithelial organoids. By inhibiting TGF-β and simultaneously activating WNT and BMP to promote the formation of parietal cells in vitro, stem cells were induced to differentiate into lateral plate mesoderm, acquiring the potential to form both cardiac and visceral mesenchyme. Subsequently, retinoic acid was added to induce the differentiation of lateral plate mesoderm into visceral mesenchyme. (Figure 1)

Figure 1. Method for Constructing a Dual-Germ-Layer Gastric Organoid

Subsequently, the authors integrated the mesenchymal cells with the epithelial organoid. Testing on gastric antrum organoids revealed that when mesenchymal cells were integrated into human gastric antrum organoids at a concentration of 50,000 cells per well and in a ratio of 2:1 with epithelial cells, a stable mesenchymal layer could form around the epithelia. (Figure 2)

Figure 2. Immunofluorescence Staining of Dual-Germ-Layer Organoid

However, despite the integration of mesenchymal and epithelial organoids, the glandular structure with single-layered columnar epithelia could not be simulated when compared to the complete human structure. Therefore, the authors added ectoderm-derived structures to the dual-germ-layer organoid. Firstly, they prepared ectoderm-derived enteric neural crest cells. Subsequently, these neural crest cells were assembled with mesenchymal cells and gastric antrum organoids, and after 4 weeks of culture in vitro, they were transplanted into mice for an additional 10 to 12 weeks of growth. (Figure 3)

Figure 3. Method for Constructing a Tri-Germ-Layer Organoid

Finally, to determine whether the constructed multi-germ-layer organoid could grow and form tissue structures more similar to the human stomach, the authors transplanted the organoid into the renal capsule of mice and allowed it to grow for 10 to 12 weeks. The resulting tissue was then compared to sections of a 38-week-old fetal and adult human stomach. The results showed that the presence of mesenchymal cells promoted the survival of the organoid in vivo and its growth into a smooth muscle layer. Compared to the dual-germ-layer organoid, the tri-germ-layer organoid with added neural crest cells was able to form glandular structures similar to those found in human stomach tissue. The smooth muscle layer was arranged in an orderly fashion, with neurons embedded within it to form a plexiform neural network, which was consistent with the structure of a 38-week-old fetal stomach and demonstrated multiple types of gastric antrum cells. (Figure 4)

Figure 4. In Vivo Construction of Multi-Germ-Layer Organoid and Comparison with Human Stomach Structure

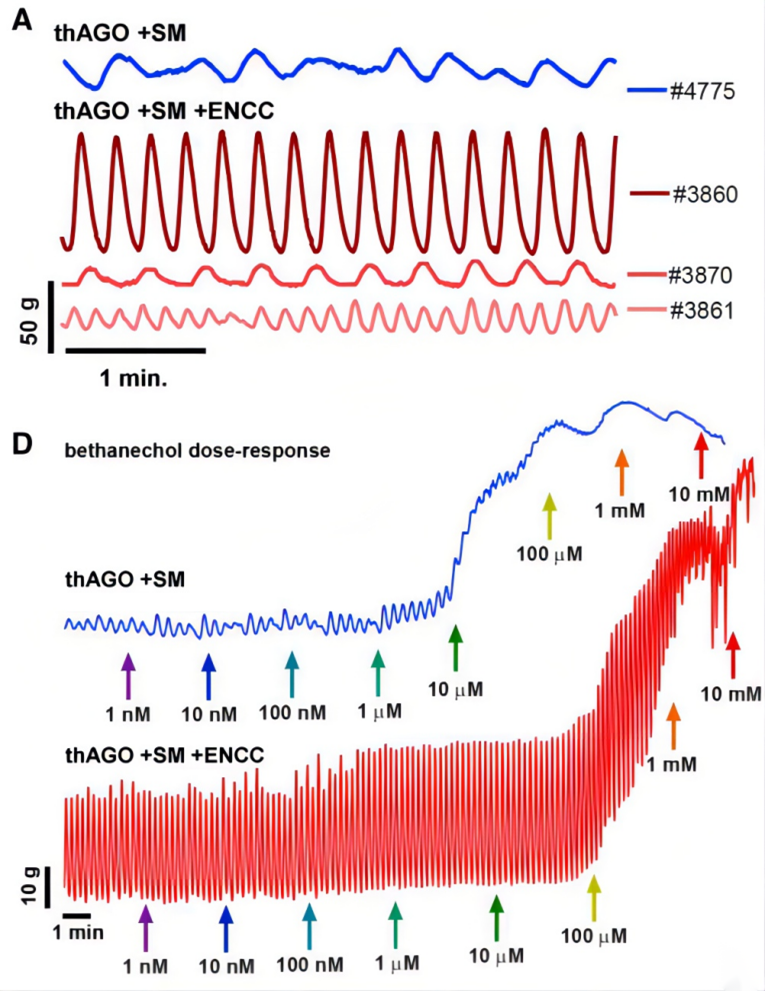

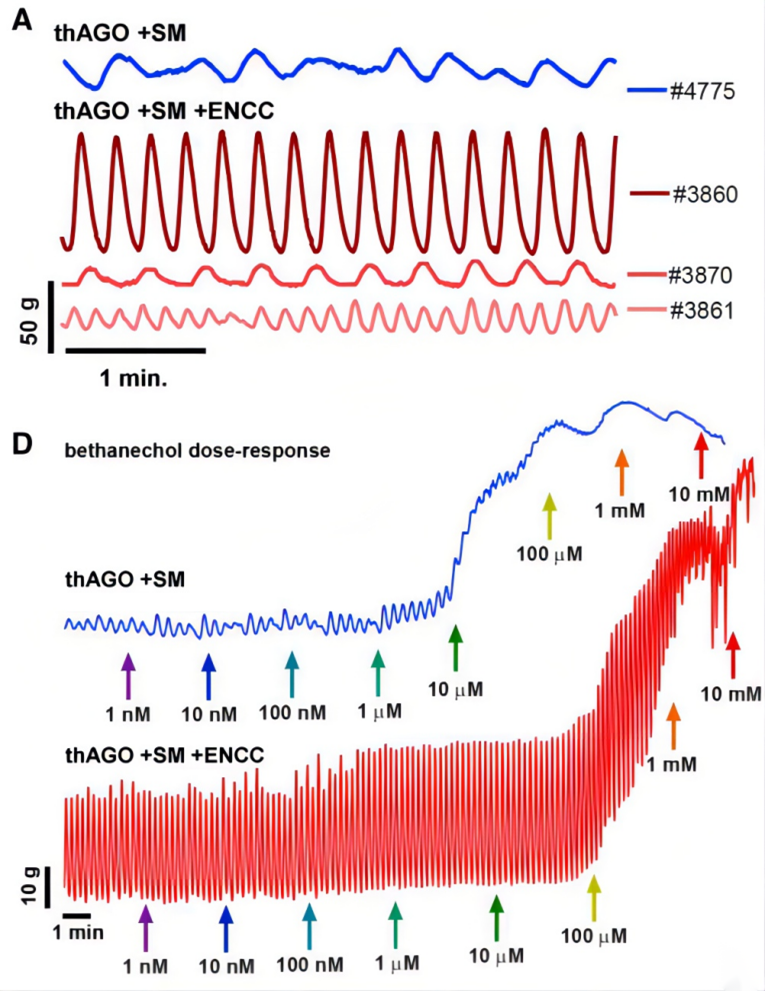

The staining comparison demonstrated a high structural similarity between the organoid and the human stomach. Subsequently, the authors investigated whether the organoid, which possessed neuromuscular units, exhibited functional similarities to the stomach in terms of smooth muscle contraction. Tissue strips were isolated from the organoid and placed in an organ bath chamber system to test their contractility. Both the dual-germ-layer and tri-germ-layer organoids exhibited spontaneous contractile oscillations, indicating the presence of interstitial cells of Cajal (ICC) that mediate communication between the autonomic nervous system and smooth muscle in both types of organoids. However, the contractile activity in the dual-germ-layer organoid was irregular, while it was highly regular in the tri-germ-layer organoid with neural crest cells.

Finally, the authors further verified the functional and structural integrity of the constructed multi-germ-layer organoid by adding agonists or antagonists such as methacholine and scopolamine. (Figure 5)

Figure 5. Smooth Muscle Contraction Test of Multi-Germ-Layer Organoid

Figure 5. Smooth Muscle Contraction Test of Multi-Germ-Layer Organoid

This study developed human gastric organoids assembled from tri-germ-layer cells derived from human pluripotent stem cells, which contain a functional enteric nervous system, smooth muscle layer, and differentiated glands. It demonstrated the feasibility of constructing multi-germ-layer organoids and provided a powerful example for the development of other organoids. Currently, organoids constructed in laboratories contain various types of cells combined into different 3D structures, but they are limited to single-germ-layer structures and lack various factors required for complete organs, such as nerves, blood vessels, glands, or immune cells, greatly limiting their ability to mimic human bodies in research. The multi-germ-layer organoid constructed in this study integrated mesenchymal cells, neural crest cells, and epithelial organoids to create an organoid with glands, smooth muscle, and nerves. Although it does not fully mimic human organs, it demonstrates the advancement and remarkable potential of organoid technology. The imperfections also represent opportunities for development. Although the organoid constructed in this study includes a tri-germ-layer structure, differences in the growth processes of the different germ layers greatly affect the connections and interactions among them. Additionally, in vitro culturing remains a challenge that needs to be overcome.

Therefore, it is the mission of BoZhen Biotech, a company with internationally leading organoid technology, to achieve the in vitro construction of organoids with synchronous development of the three germ layers, decipher the interactions between tissues and organs during human development, recreate them in organoids, and promote the continuous development of organoid technology.